The Meek Really Did Inherit the Earth, at Least Among Ants

How Ants Conquered the World—It May Be a Matter of Skin

When we picture domination, towering predators or advanced machines usually come to mind. Yet the true masters of the planet are tiny, industrious insects that have silently colonised almost every corner of Earth: ants. Their success isn’t rooted in brute force or sophisticated technology, but in something far more subtle—their skin.

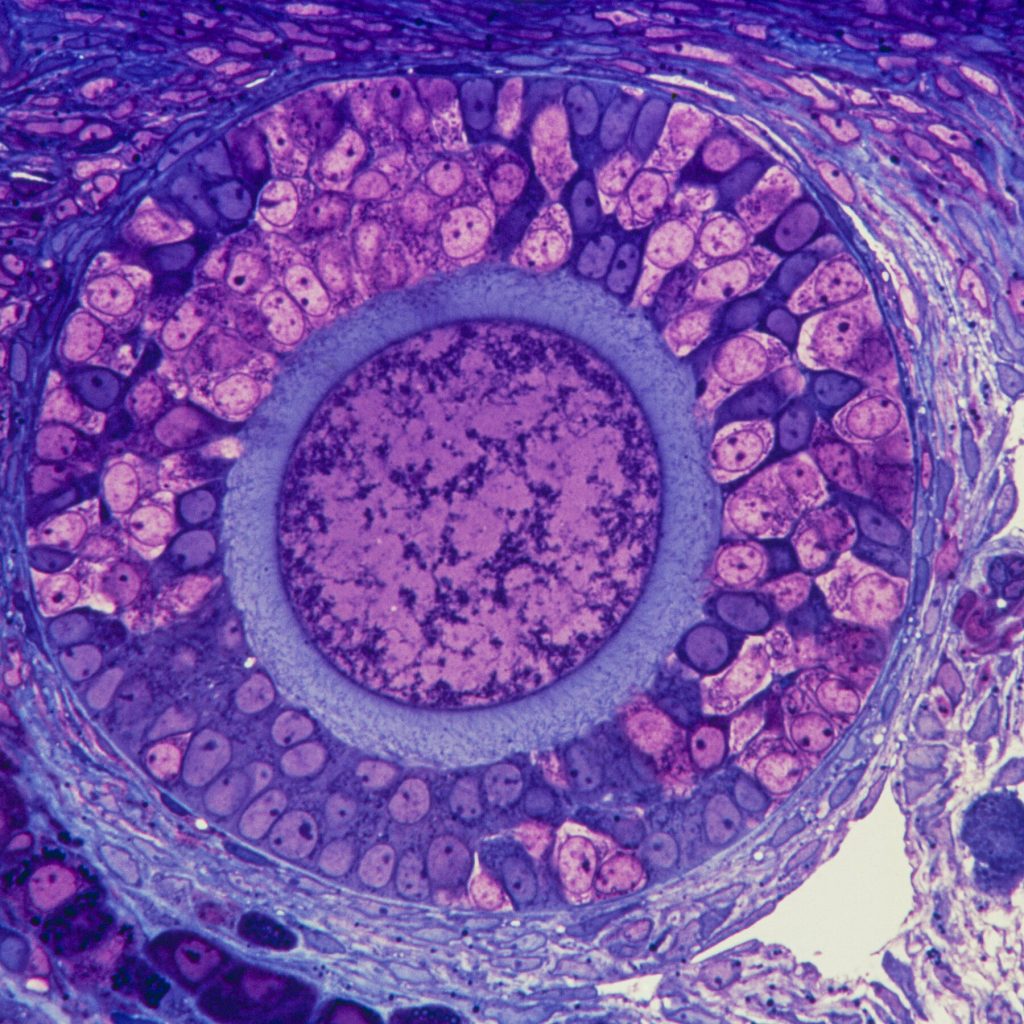

Ants are covered in a resilient exoskeleton made of chitin, a natural polymer that provides both protection and flexibility. This skin acts like a miniature suit of armor, shielding them from predators, harsh climates, and even chemical assaults. It also enables ants to carry loads up to 50 times their own body weight, a feat that would be impossible without such a sturdy exterior.

Social Structure Amplifies Their Advantage

Beyond their physical armor, ants excel because of their highly organized societies. Each colony functions like a well‑run corporation, with workers, soldiers, nurses, and queens all performing specialized roles. This division of labor, combined with the durability of their cuticle, allows colonies to adapt quickly to environmental challenges and to exploit resources that larger animals overlook.

Ecological Impact and Human Relevance

Ants play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, soil aeration, and pest control. Their foraging activities redistribute organic matter, enhancing soil fertility and supporting plant growth. Moreover, studying ant exoskeletons has inspired biomimetic materials for engineers seeking lightweight yet strong composites for aerospace and medical applications.

Conclusion

While the phrase “the meek inherit the Earth” may sound poetic, ants embody it in a very literal sense. Their seemingly simple skin is the cornerstone of an evolutionary strategy that has turned them into the planet’s most successful terrestrial colonisers. In the grand tapestry of life, the smallest threads often hold the greatest strength.